When AI routing breaks our assumptions

I experienced something maddening recently. My MCP server’s semantic search tool was returning wildly different responses to identical requests: verbose academic analyses in the morning, terse bullet points by afternoon. Same prompt, same parameters, completely different outputs. After some digging, I realized what many have learned by now: even when using a single frontier model provider, we are not talking to one AI model anymore. We were talking to a routing layer that is silently switching between multiple models based on load, cost, or some other invisible logic we can’t control. And you know what? I ❤️ it.

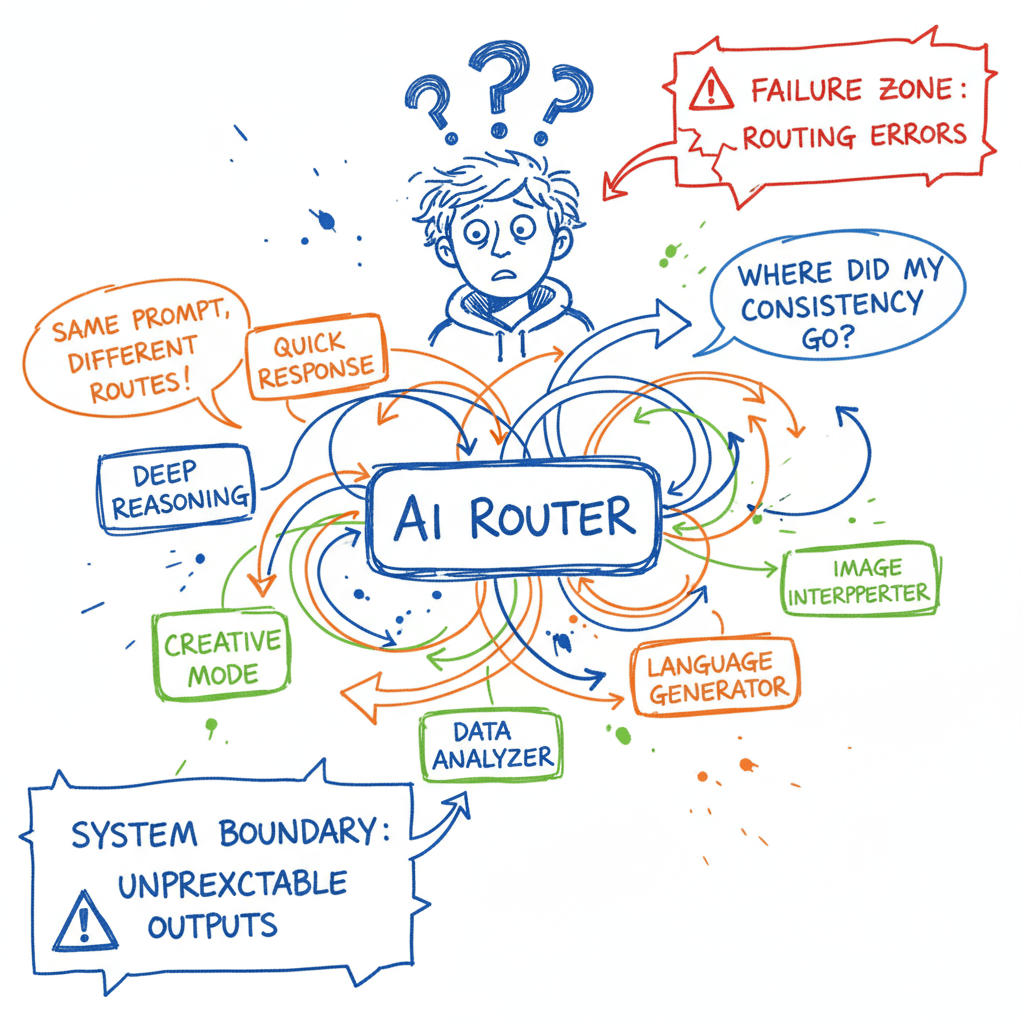

The invisible traffic controller

This isn’t a bug in our implementations. It’s the new reality of how AI providers are scaling their services. Behind that single API endpoint we’ve been calling may sit an entire fleet of models, some optimized for speed, others for depth, some for cost-efficiency. A routing layer decides which one handles our request, and we have zero visibility into that decision.

The implications for MCP server design are immediate and profound. When our tools can’t predict which model will process their outputs, we lose a fundamental assumption about consistency. That carefully crafted prompt template we spent days perfecting? It might work brilliantly with the reasoning-optimized model and fail completely with the speed-optimized one. Our response parsing logic that expects structured markdown? It breaks when the lightweight model returns plain text.

Reality check:

Routing unpredictability is the best thing that could have happened to MCP development. It’s forcing us to build exactly the kind of bulletproof, assumption-free tools that autonomous agents will need. We’re learning to engineer for chaos before the real chaos (agents calling our tools thousands of times in ways we never intended) even begins.

Engineering for unpredictability

I’ve started to rework my mcp-factcheck MCP server and treating this routing variability as a first-class design constraint. That MCP server now implements what I call “defensive tool design”: every exposed method assumes the least capable model might respond. I am enforcing strict JSON schemas for all responses, even when it feels like overkill. I’ve added retry logic that subtly reformulates requests when it detects terse responses to complex queries. Most importantly, I am adding a cache to successful response patterns and reusing them as templates when possible.

The most counterintuitive lesson has been that simpler tool interfaces actually handle routing variability better than sophisticated ones. A tool that asks for “analyze this text and return three key points in JSON” gets more consistent results across different models than one asking for “perform comprehensive analysis with methodology explanation.” The constraint forces even the most capable models to return predictable outputs, while giving weaker models a clear, achievable target.

ATTENTION

For a comprehensive guide on handling this chaos, I’ve compiled 15 battle-tested strategies to mitigate AI routing unpredictability that go beyond defensive design.

Decomposition as defense

This routing opacity is reshaping how I think about robust MCP server architecture. I’m moving away from designing (and consuming) tools that assume consistent model capabilities and toward tools that gracefully degrade. My semantic search tool for fact-checking exemplifies this: rather than one complex “analyze_and_verify” endpoint, it breaks down into atomic operations: claim extraction, source retrieval, credibility scoring. When a lightweight model gets routed to it, it can still handle the simple semantic matching. When a reasoning model is invoked, it can orchestrate these primitives into sophisticated verification chains.

Pattern I'm seeing:

MCP servers with 10+ simple, focused tools are outperforming those with 3-4 complex, multi-purpose tools. The simpler tools act as stable primitives that work regardless of which model responds, while complex tools become points of failure when they hit an underpowered model.

The broader pattern here is that we’re no longer engineering for a specific AI capability. We’re engineering for a probability distribution of capabilities, where any given request might hit the genius model or the intern model, and our systems need to work regardless. It’s a fundamental shift in how we’ve been approaching AI integration so far: less about optimizing for the best case and more about surviving the worst case while still delivering value.

Principle of Least Surprise

What we’re discovering through routing chaos aligns perfectly with my Enterprise DB conversation about designing for unpredictable systems. In the article Beyond Protocols: Why the ‘Principle of Least Surprise’ is the key to engineering AI systems | EDB I argue that with AI, “we need to account for unpredictability” and focus on “managing behavior, not just data.” Routing variability proves this point: we’re not just piping data through different models; we’re managing wildly different behavioral patterns from the same endpoint.

Building for the new normal

As MCP servers become critical infrastructure in AI applications, this routing-aware design philosophy isn’t optional anymore. It’s the difference between systems that work in demos and systems that shine in production. We’re learning to build tools that don’t just serve AI, but adapt to its increasingly complex and opaque operational realities.

The irony isn’t lost on me: we’re using AI to build more intelligent systems, yet we’re having to dumb down our interfaces to accommodate the intelligence we can’t predict. But that’s the engineering reality we’re in. The models are getting smarter and dumber at the same time, depending on when we catch them. Our job is to build systems that thrive in that chaos.

Have you had to rework your AI tools because of these recent changes?

Ready to implement these ideas?

Check out my tactical guide: 15 battle-tested strategies to mitigate AI routing unpredictability, from prompt engineering patterns to full architectural solutions.